More than five years after its emergence, Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) has transitioned from a devastating acute pandemic to a persistent, endemic global health challenge.1 As of 2025, the global response has shifted from emergency containment to sustained management, guided by a deeper, albeit still incomplete, understanding of the virus and its long-term implications.2 While widespread vaccination and acquired immunity have dramatically reduced mortality, SARS-CoV-2 remains a “constant threat”.3 The 2025 landscape is defined by this new phase of management, which is focused on mitigating severe disease, addressing the chronic burden of Post-COVID Conditions (Long COVID), and navigating significant, unresolved scientific and political controversies.4

The Evolving Biology of SARS-CoV-2

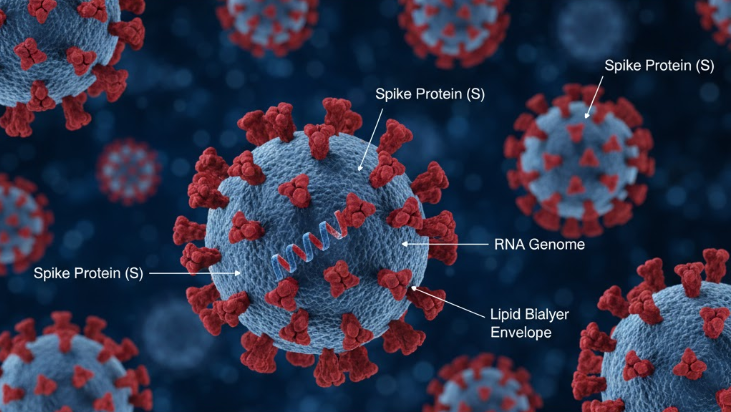

SARS-COV-2 Virion Structure ~ 100 nm

COVID-19 is the disease caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), a single-stranded, positive-sense RNA virus belonging to the Betacoronavirus genus.6 Like all viruses, SARS-CoV-2 is “constantly changing”.7 This rapid evolution has been the defining feature of the pandemic, leading to a succession of variants of concern with increased transmissibility and altered pathogenicity, including Alpha, Beta, Delta, and Omicron.8

By 2025, the viral landscape is dominated by the Omicron branch.8 Public health interventions are now in a constant race to keep pace. The 2024–2025 generation of COVID-19 vaccines, for example, was specifically formulated to “more closely target the JN.1 lineage” of the Omicron variant.10 This evolution has fundamentally changed the clinical nature of the disease. While pre-Omicron variants were known to target a wide array of organs, the combination of vaccination and Omicron’s dominance has resulted in a “less morbid condition for many”.1 However, moderate and severe acute disease is still observed, and the virus continues to pose a significant risk to vulnerable populations.1

Clinical Profile: Transmission, Incubation, and Symptoms

Transmission Dynamics in 2025

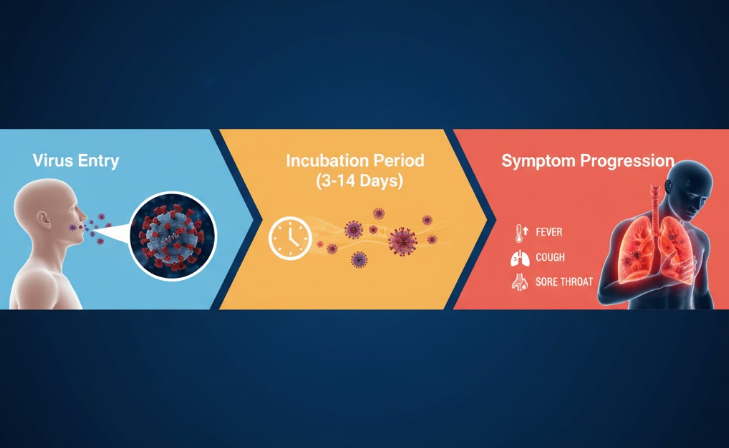

The primary mode of SARS-CoV-2 transmission is airborne.12 It spreads when an infected person breathes out droplets and “very small particles” (aerosols) containing the virus, which are then inhaled by others or land on their eyes, nose, or mouth.7 Critically, infectivity is highest during the early stages of infection, particularly in the 1–2 days before symptoms begin and within the first few days of symptom onset.6 This high rate of presymptomatic and asymptomatic transmission remains a primary driver of its spread.6

The risk of transmission is not uniform across all settings. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), the risk is highest in “crowded and inadequately ventilated spaces”.13 This has been confirmed by systematic reviews, which found that the highest secondary attack rates (SARs) occur in community indoor settings involving activities like singing (SAR 44.9%), indoor meetings (SAR 31.9%), and fitness centers (SAR 28.9%).14

Incubation Period Variance

The incubation period—the time from exposure to symptom onset—has shortened as the virus has evolved. The WHO and U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) maintain a broad “classic” range of 2 to 14 days, with an average of 5–6 days.15 However, research demonstrates clear differences between variants. The incubation period for the Alpha variant was approximately 5 days, shortening to 4.3 days for Delta. The now-dominant Omicron variant has the shortest incubation period, averaging just 3 to 4 days.18 This accelerated timeline complicates contact tracing and public health interventions, as individuals become infectious more quickly after exposure.

Symptomatology and Disease Severity

As of 2025, the clinical presentation of COVID-19 is highly variable, ranging from asymptomatic infection to critical, life-threatening illness.1 The WHO states the most common symptoms are now fever, chills, and sore throat.15 The CDC maintains a broader list of possible symptoms, including cough, fatigue, muscle or body aches, new loss of taste or smell, shortness of breath, congestion, nausea, and diarrhea.17

For clinical management, the U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) classifies COVID-19 severity into five distinct stages 1:

- Asymptomatic or Presymptomatic: A positive test without clinical symptoms.

- Mild Illness: Presence of symptoms (e.g., fever, cough, malaise) without shortness of breath (dyspnea) or abnormal radiological findings in the lower respiratory tract.

- Moderate Illness: Evidence of lower respiratory tract disease, either clinically or radiologically, but with an oxygen saturation (SpO2) of 94% or higher.

- Severe Illness: Defined by an SpO2 $< 94\%$ on room air, a high respiratory frequency ($> 30$ breaths/min), or significant lung infiltrates ($> 50\%$).

- Critical Illness: Includes patients who develop acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), respiratory failure, septic shock, or multiple organ dysfunction.

While progression to severe or critical illness has become rare for vaccinated and otherwise healthy individuals infected with Omicron, it remains a serious threat for the elderly and immunocompromised.1

Global Health Status and Public Health Strategy (2025)

By late 2025, the global health status reflects a new, endemic reality. While the virus is still circulating, as evidenced by WHO global sentinel surveillance showing a 5.6% test positivity rate in October 2025 19, the catastrophic impact of the early pandemic has subsided. National dashboards, such as India’s Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW), reported only 11 active cases nationwide as of November 3, 2025, signaling a transition to a low-level endemic state.20

This shift is reflected in global health policy. The WHO is actively developing a new Strategic and Operational Plan (2025–2030), explicitly designed to move global efforts from “short-term emergency response to sustained, integrated programming”.2 In the U.S., the CDC has simplified its public advice to focus on “Core Prevention Strategies,” which include staying up to date with vaccines, practicing good hygiene, and taking steps for cleaner air.22 The primary tool remains vaccination, with recommendations for the 2024-2025 vaccine 10 and risk-based guidance being formulated for the 2025-2026 season.23

Ongoing Controversies and Scientific Uncertainties

The Unresolved Origin of SARS-CoV-2

The most significant and politically charged controversy remains the origin of the virus. As of 2025, a “vigorous scientific debate” continues between two primary hypotheses.4 The “natural spillover hypothesis,” which posits animal-to-human transmission, is the most widely supported theory and is backed by numerous genomic and evolutionary analyses.4 This is contrasted with the “lab-leak theory,” which suggests an accidental escape from the Wuhan Institute of Virology (WIV) and is supported by “circumstantial evidence” (e.g., the outbreak’s location, high-risk research).4

This scientific question has been deeply complicated by geopolitics. In April 2025, the White House officially declared that COVID-19 originated from a laboratory in Wuhan.4 This move was criticized in scientific journals as a “case where political considerations have influenced… scientific matters,” undermining the objective, evidence-based pursuit of truth.4

The Challenge to Public Health Credibility

The politicization of the pandemic has contributed to a secondary crisis: an erosion of public trust in health institutions. In 2025, “organizational upheavals” and disruptions at the CDC have led to concerns about its “professional credibility”.26 In a direct response, the Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy (CIDRAP) and The New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) launched the “Vaccine Integrity Project.” This independent body aims to provide transparent, scientifically sound data for the 2025–2026 vaccine season, effectively creating a parallel source of information to bolster public trust.26

The Enigma of Post-COVID Conditions

While the acute phase of COVID-19 is well-understood, the greatest scientific uncertainty in 2025 is the mechanism of Post-COVID Conditions (Long COVID). This syndrome is highly prevalent; a 2024 systematic review showed a global pooled prevalence of 36%.27 Its impact is severe, with research from the RECOVER initiative demonstrating it can increase an adult’s risk of developing new, serious health problems, including chronic kidney disease.5 Despite this, its underlying cause remains an enigma. The leading theory of “viral persistence” in the body “can’t explain all cases,” leaving a critical gap in medical knowledge.8

Conclusion

In 2025, COVID-19 is a manageable endemic disease, but it is far from a solved problem. The global health community has successfully shifted its strategy from emergency response to sustained management, relying on updated vaccines and core prevention strategies to control acute illness. However, the path forward is complicated by three distinct challenges: the biological challenge of a constantly evolving virus, the profound clinical burden of Long COVID, and the socio-political challenge of scientific controversies that have eroded institutional trust. Effectively managing the long-term threat of SARS-CoV-2 will require navigating all three.